Padmasana, better known as lotus pose, is the quintessential yoga pose. While the cover of yoga magazines often feature arm balances and warrior poses, those poses are nowhere to be found in ancient yogic texts.

The Hatha Yoga Pradipika features only six poses, all of them seated, and padmasna first. Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras define yoga asana as a steady comfortable seat.

When thinking about padmasana, it’s useful to keep in mind that the ultimate goal of yoga is not physical fitness or even mental and emotional stability.

Regardless of particulars of lineage, the ultimate goal of yoga is liberation from ignorance of our true nature; it is recognition and (re)union with ourselves as part of the universal consciousness.

Patanjali’s description of yoga as a steady comfortable seat is a perfect explanation of the value of padmasana. It is not uncommon for Himalayan yogis to sit in meditation for days at a time, and padmasana allows a yogi to sit steadily for long periods of meditation with a properly aligned spine and without fear of falling over.

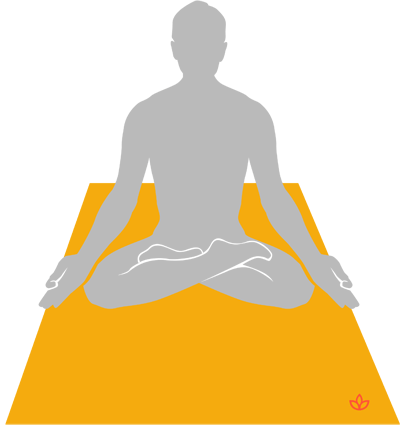

What Does Padmasana Look Like?

Padmasana is a seated pose in which each ankle is crossed over the opposite thigh. This requires a crossing of the shins that essentially locks the legs in place. Indeed, many people who force their legs into lotus pose have trouble getting them back out without also using their hands to help.

In padmasana, the spine is long. The crown of the head reaches up toward the sky, the chin is gently tucked so that the back of the neck is long while the chest is open and the shoulder blades are drawn toward the spine.

The hands and arms can assume many different gestures. We will discuss them as placed on the knees, palms face-up.

Benefits of Padmasana

While it is less common for people in the West to meditate for hours and hours at a time, it was and is a standard practice in meditation retreats. (Learn more in Detoxing From Stimulation: Learning Patience and Trust Through Vipassana Meditation.)

In some traditions, monks spend years at a time in a small meditation space. It's natural for a body to get tired; padmasana provides such a stable base, that even if the meditator falls asleep, he or she won't fall over.

For those of us who are not monks, this stability helps us to sit in stillness for longer periods without needing to readjust the body.

With less attention going to physical discomfort and adjustment, there's more attention for meditation. This, of course, only holds for bodies that are comfortable in padmasana.

Can my Body Actually do That?

The best posture for meditation is a non-injurious one, in which your attention is not hoarded by pain and discomfort. (Learn more in Get Your Meditation Posture on Point in These 3 Poses.)

That means that for many people, especially people who come to yoga after childhood or early adulthood, safely doing lotus pose will either take a long time or not be an accessible option.

It’s worth remembering that the purpose of lotus pose is to support concentration, meditation, and samadhi. If it’s making a person miserable or causing them pain, it isn’t filling that roll, and it would be better to find another, more comfortable position.

Be Prepared to Transform Your Body Slowly

To do lotus requires extreme flexibility in the hips, knees and – in the learning stages – also the ankles, as well as strong deep core muscles to hold the spine long and prevent injury or strain to the lower back. (Learn more in Bend Without Breaking: 10 Yoga Poses to Increase Flexibility in Body, Mind, and Spirit.)

Preparing the Body

To do padmasana, a body that needs to be able to comfortably flex and extend the feet, squat deeply (malasana), sit in staff pose (dandasana), and recruit strength through a significant range of hip motion.

Do these preparatory exercises for as long as it takes for these exercises to be completely comfortable.

For Dandasana:

The body must be able to sit up tall with a long spine. If the hips are elevated by a blanket in dandasana, it’s a good draft to keep them elevated when working on other seated poses.

Ankle circles:

Seated in dandasana, cross one foot over the opposite and use the hands to move the ankle in circles.

Hip circles:

From dandasana, bend one knee and hold the leg by the foot or shin and the thigh. Use the hands to move the hip joint in large circles in each direction.

Stretch the Back:

The muscles along the spine need strength in every direction. One option is to seated forward fold, boat pose (navasana) and a side bending series, such as swaying palm tree pose (standing with arms overhead, leaning to one side while keeping the spine long and without breaking the line of energy at the hip).

Another option is to do a similar series of motions seated: with leg spread wide enough to feel stable, extend the arms and join the hands in front of the torso, moving the hands and torso in large circles each way.

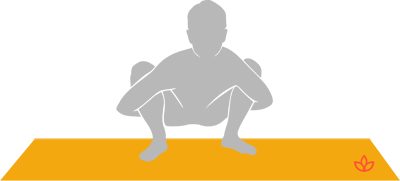

For Malasana:

Many knees and ankles will require years to reach the deep squat of malasana asks.

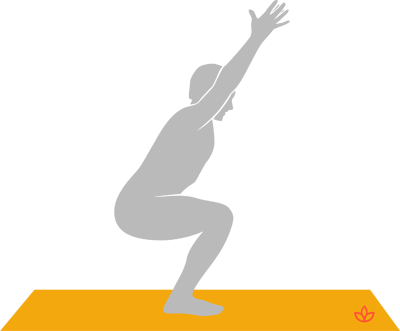

To prepare and strengthen the body for malasana, practice utkatasana (chair pose) until the pose becomes comfortable.

When ready, try doing malasana with blocks beneath the seat, and then, for increasing increments of time, try the pose without the blocks.

Practice Half Lotus

To cross one ankle over the opposite thigh and place the other beneath the thigh opposite it is called half lotus. Begin to practice half-lotus, being sure to do both sides. Practice meditating in this posture.

Final Thoughts

Once you can comfortably do half-lotus on both sides and all the preparatory poses, you can begin to experiment with short sessions in full lotus. One thing to keep in mind: the goal of lotus is support for meditation.

To train the body to do padmasana, without training the mind to concentrate and meditate, is like aspiring to be a cardboard cut-out of an action figure.

The pose is to support meditation.

Therefore, deepening one’s meditation is the ultimate sign of success in padmasana – or any other seated meditation pose.

During These Times of Stress and Uncertainty Your Doshas May Be Unbalanced.

To help you bring attention to your doshas and to identify what your predominant dosha is, we created the following quiz.

Try not to stress over every question, but simply answer based off your intuition. After all, you know yourself better than anyone else.